ONYIS MARTIN: TALKING WALLS - Curator Sabo Kpade

Transdecollage: Onyis Martin in conversation with Curator Sabo Kpade

The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Thinking art historically, your torn poster technique is reminiscent of decollage championed by nouveau réalisme of 1960s France, with nods to Lettrism moment of 1940s, also in France. Are these reference points for your Talking Walls series?

Basically, for me, I've always been interested in what people are writing on the walls. As much as words are figurative in mind, they are also abstract. That is to mean one we filter words based on our past experiences, and our surrounding. Our mind filters based on what we know. As much as we are reading the same thing, I think we get somehow different meanings. My interest started from questioning, for example, who is writing? Who is it being written for? And so it's about accessibility or availability of information and what we do with the information.

When thinking of your Talking Walls paintings one good reference for me is Robert Rauchenburg’s Combines (1954 - 1964) and its blurring of art production and “ordinary” materials. Is this a fair comparison?

I think basically what fascinates me about Robert Rauchenburg's work is his use of different materials, the space where you are not afraid to explore, to be confident with different mediums and to use them in a way that it's in cohesion. His Combine series borrows from nature, and you see it borrows from the environment. It's very direct. It gives you symbols that you can relate to without necessarily trying hard. It's a very universal language when the symbols are direct and you can relate to no matter which country you're coming from.

What drew you to the photographs used in works such as 63 - Downtown (2019) and 91 (2019)?

Because that is what I could get from the photo studio. I only got the two pictures but then I started to remove parts of it. Sometimes, I take an eye out. Most of the time it's not the whole head. It gives both the impression of someone watching and the impression also of a lost child.

Any reason why you stopped using one photograph and continued using the other in more recent paintings?

The resemblance, because most people think it's me. So as not to attach a biography. I tried to remove that attachment between the portrait and me. To create a situation where painting then stands on its own. Now I have a photo of me from when I was young, and I'm trying to edit it so that I become a part of future painting.

Sympathy, pity or some other such identification is hard to dismiss once fixed on the image of the boy-child in Nº 86 - Keep Your City Clean (2019). I wonder what emotional identification you aim to establish when using the face of a child?

This could be a lost child who is begging to be found or to be seen, but also it could be also dead. I want to create a mood where you want to really go deep into the painting to see but the wall is still innocent. When the child is born, the child knows nothing. Just like the wall, it gets a lot from the community or the society. This pasting of information on walls becomes what the child gets from the society. Sometimes the child keeps some of this information they get from the society as their reality. It is there to question what we believe in.

One could say that by 2016 you were still experimenting with materials and themes to prioritise in the Talking Walls paintings.

Yeah, it was very experimental, but it was also the period that I was learning and gathering a lot of materials that I would use in the Talking Walls paintings. From this period, almost everything from the walls I see on the streets is put in one painting. It could look very well curated, but there's a lot of information in one space or in one painting. This was after finishing my residency from South Africa. I was more looking into African figures who've changed spaces where they are from anti-apartheid figure Steve Biko, slain Burkina Faso leader Thomas Ankara and environmental activist Wangari Maathai.

These early paintings are crowded with information be they maxims, found images or number systems. By 2019, the difference is remarkable. Gone are the recognisable political figures. Letters and images are increasingly reduced or distorted. A new syncretic form begins to emerge. Did your confidence simply improve?

When I'm working, I'm constantly looking at how I can express the same thing in the simplest way. At first, I was collecting a lot of information to put into one painting. For example, in N 8901-Ladies Are Always Right (2019) is clearly a poster notification of CCTV surveillance. There's a face of a kid. There's so much element of showing you that someone in the wall is looking. I later discovered that I could put a part of the eye to communicate the same thing. So, I'm constantly looking at how much I can remove what is not necessary. If this element was not there, would the painting still communicate? So, it's more of a lot of self-reflection, a lot of talking with other artists without necessarily telling them what I'm thinking of. I think basically for me, the reason why I'm removing a lot of the posters is to allow the audience to look at the work in a way that you are not being directed by the artist, very much. So you’re not being force-fed in order to give the audience the space to think or to make their own opinion also.

The term “witch doctors” has a negative connotation about seeking bad luck or evil against others. Is “herbalist” a better term? And don’t people also go to these “doctors” for good health or good luck?

The doctors in Kiswahili are called Mganga which technically means a doctor. Most of these doctors are herbalists. But the fact that during British colonial rule in Kenya, they were labelled as negative, and I think people don't want to be associate with them. To go to these “doctors” would mean that you're not on the side of God. This is also from Christian missionaries' teachings.

Are you only interested in the posters from the herbalists?

nIt's very interesting because at first, I was comparing all angles of what we're consuming by way of advertisement posters. Later, I started to include posters from entertainment, clubs and casinos. Then I started questioning the more dominant posters from the street which were those of witch doctors. But I was also showing this full frontal, showing people what they see every day, but lie to themselves that they don't see. It's something that you know is there, but nobody accepts, or nobody acknowledges. If you are in a room of let’s, say, 10 people and you ask them if they use these witch doctors, nobody accepts. But these posters are always pasted on the walls every week which means somebody is consuming them, somebody is using them.

Just how widely advertised are the posters Nairobi and how widely, even when secretly used, are witch doctors or herbalists, as the case might be?

These doctors or herbalists cannot be using their money to print, to employ people to paste the posters across the country because you get them anywhere, across the country for no reason. I've seen them also in Uganda. You go across Africa, you see them. So, it means that they have market. But it also to show this consumerism that no one wants to acknowledge. It goes back to our pre-colonial history. It starts conversations on African spirituality practices. I have a lot of people come into the studio and have this reflection. They just occupy that space and start to negotiate on issues that are not always directly linked.

Is this also a commentary on religion? I’m from Nigeria and it’s been said that the country is 50% Christian, 50% Muslim, and 100% traditional?

Yeah, it's also commentary on religion because even in Kenya, where Christians are the majority, you will find even the people who don't go to church will still follow Jesus. They'll not comment negatively about the church. So, they're very captured in that way. What is very interesting also is that most people are still traditional. You'll find somebody having a Christian wedding and still go to do a traditional wedding. Or start with a traditional wedding and then do a Christian wedding. It's like a dance between the two practices.

Did you specifically only seek out posters by these “doctors”?

When I was starting, I mixed. I was more looking at consumerism mixed with capitalism. That's also one reason why there was a lot of posters when I was starting. I was comparing for example, old and new posters of Blue Band Margarine. I was looking at how design in advertising has changed from what our fathers were consuming in the 1980s and what is appealing now.

And these posters, have you ripped them off from walls om Nairobi streets yourself?

Yeah, the posters, I take them from the streets myself. Usually, in the first days of the week, so that will be Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, because on Sunday, they put them back new ones. The Talking Walls paintings work is a constant negotiation between parties. The removal of the posters can bring about this negotiation. For example, if I take the posters from the street, some people in that space will be like, “he’s cleaning the environment”. Or maybe they will even confuse me for someone working with the county to clear the walls of posters. That's one way of negotiating this. The other way to negotiate this will be the printers or the doctors putting up the posters. For them, what I’m doing is stealing or clear vandalism.

What is the social makeup of the neighbourhoods from where you source posters for the Talking Walls paintings?

It basically doesn't matter, but the posters are more in lower income areas. When you go to middle class area, it becomes a bit less. In higher income areas, they're there, but you won’t always see them. Also, because in very high-income areas, there’re a lot of signs saying “no poster or you will be fined”.

It means something that this language of instruction is only found in lower income areas. There's something about social control that you’re arriving at. I wonder if you're also thinking about accessibility, social norms, formal and informal.

I’m exploring how these instructions are working in different spaces. For example, in higher income areas, there's going to be a particular person who sees to it that there are no posters. While in lower income areas, I think the posters are still there because nobody is coming to check.

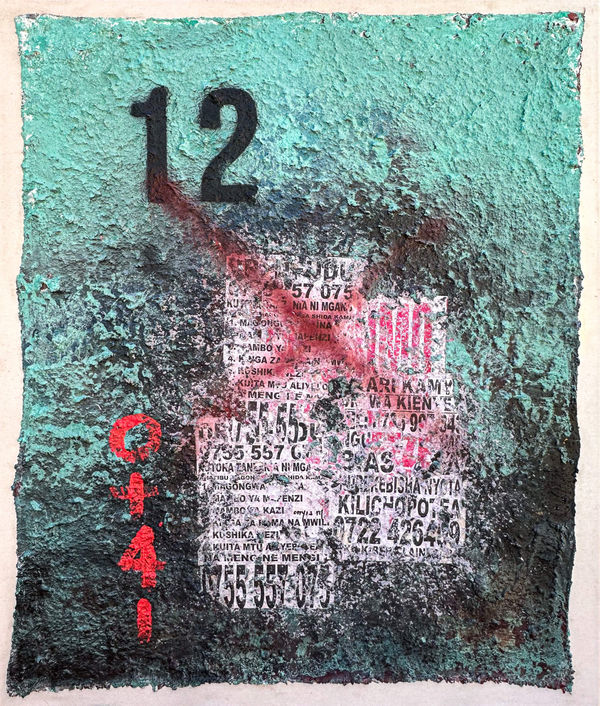

What methods are you using to apply paint and control colour?

The creation of my work is very performative. I start by doing the different layers of paint until I'm happy with the texture. I start with a different colour, then layer another colour on top, and another colour on top. So, it's more of layering colours on top of each other. This layering of different layers to hide what was before is almost like erasing history. The canvas now becomes like an archaeology site. If you want to know what was before, you must dig in. Sometimes I remove parts of the paint to expose just bits of colours that were laid before. Sometimes the finishing is, like I told you, using very liquid paint so that it doesn't cover everywhere.

With so much layering to do in one painting, is more care and control required or is it a freewheeling process for you?

When I'm looking at a particular wall from any street in Nairobi, I'm also trying to see the layers of paint which has accumulated over years and decades, so I'm imitating that. And the final layer is when I'm limiting. I'm just pouring in the places that I want it to be. And then using a water spray to spread the paint around. So, it only goes to very tiny spaces. Another thing that I also use is charcoal. So, I rub charcoal, dust the canvas and then spray with the water spray. So, it spreads on the canvas and then I leave it overnight to dry, and then just use a fixer tip to fix everything. At this stage, there are no posters. The poster comes after.

The rough surfaces on the Talking Walls painting, how do you achieve that exactly?

So, it's a mixture of paint. It's a mixture of acrylic, glue, and a bit of paper.

Do you ever see yourself making the full jump to abstraction?

My goal is to get to full abstraction.

And you can't just jump to that point now?

No, I'm not ready. I'm still learning. Sometimes people say, with this texture, you could use very nice colours that are so appealing to people. But then it loses that wall aesthetic and becomes a wall hanging that will match with the colour of a couch. I want someone to look at the wall and feel like it's a space that they've seen in their backyard or for people to relate to, not necessarily for people to match with something in their house.

So far, are the people who have bought or are interested in the Talking Walls paintings been those type of people?

Most of the people that are buying are doing so because they really like the work as it is. I think the only time I had a problem was when a lady who came to the studio to buy a piece of work but whose husband said he cannot have “Juju posters” in the house. He said I must try to remove one particular poster. I didn't remove it. I told the wife that I cannot change the painting. So, if you're good with it, it's okay. If you're not, it's also fine not to buy it. She eventually bought it. I don't know if husband and wife are still together.

Let’s hope they are. Percentagewise, how much of the final painting is a controlled product and how much is left to chance?

I want almost 80% control. But when the work is done, the control is 60 to 70%. I’m also working with the painting, not fighting the painting. We are working together for us to succeed. Sometimes I fail and I must start again. Sometimes something good happens and then I follow that direction. But most of the time, it's basically working together with the painting to achieve the goal.

When you say working with the painting, are you also referring to, say, weather conditions, storage conditions, or other external factors?

The weather condition, the storage condition, but also the flow of the paint, sometimes, not going a hundred percent my way.

The posters you incorporate in your paintings are dominated by bold prints in blue, green, black and red. As a painter, what does that tell you?

The reason, I don't know. But maybe it's for visibility. Maybe it's something to do with design. This is something I'm now exploring because these people are doing their research. They know the wordings they use. They are very specific in their use of colour and font. The language is brief to the point. They are like artists doing their work, and they are doing background research on what can be easily read.

We're now talking about the efficacy of graphic design: what's legible, how information is absorbed, the speed of that absorption, too. There's a lot there.

There's a lot there. Also, when you're thinking about traditional witch doctors, in your mind, this “doctor” is a very old person that is not looking at these things. For them to be really thinking about it shows that they're doing research.

How do you decide when a work is done?

Basically, it's very hard to decide. I must stay with the work for some time because sometimes the work is done and then I walk in the street and when I come back, I see that something needs to be added. Usually, the work is finished when I'm scribbling the writings. Basically, I don't finish by using paint. The work is done when I'm writing, for example, the phrase “Kodja'au pigwe” in Kiswahili means “Urinate here, you are going to be beaten”.